Come sail away -- again

While searching for information about Atlantic crossings involving immigrants, I found an account by Gottlieb Mittleberger of his travel to America in 1750, 130 years after the Mayflower crossing. Mittleberger had been hired to be the organist and schoolmaster at the St. Augustine's Church in Providence. I don't know if that's supposed to be the city in Rhode Island.

He would take an organ with him, which he picked up in Heilbronn in southwestern Germany, not far from Stuttgart. From there he sailed to Rotterdam, the Netherlands and thence to Cowes in England. From Cowes, he sailed aboard the Osgood with 400 other passengers to Philadelphia, PA.

I was unable to quickly find any detailed information about the ship. I don't know for sure whether is was a British or Dutch ship. One account I read called it a British ship in one paragraph and a Dutch ship in the next.

He returned to Germany four years later and subsequently wrote a book about his travels and experiences in America. You should note that he produced the book in an attempt to dissuade his countrymen from making the journey:

"... the most important occasion for publishing this little book was the wretched and grievous condition of those who travel from Germany to this new land, and the outrageous and merciless proceeding of the Dutch man-dealers and their man-stealing emissaries ..." More on this in a bit.

Knowing that this might make his objectivity suspect, he wrote, "I related both what is good and what is evil, and I hope, therefore, to be considered impartial and truthful by an honor-loving world."

In all, his travels, including some stays in some of the ports along the way, lasted from May to October. The journey to America, he wrote, can take from 7-12 weeks, depending on sailing conditions. Mittleberger writes about the length of the journey by talking about how many hours a leg is from one point to another, but the numbers don't seem to relate to time as much as distance, as he states that the journey was 1,700 hours or 1,700 French miles. Look up French miles if you enjoy being confused.

He details the rigors of traveling to England, which are bad enough, but then writes, "When the ships have for the last time weighed their anchors near the city of [Cowes], the real misery begins with the long voyage."

He continues, "... during the voyage there is on board .. terrible misery, stench, fumes, horror, vomiting, many kinds of sea sickness, fever, dysentery, headache, heat, constipation, boils, scurvy, cancer, mouth-rot, and the like, all of which come from old and sharply salted food and meat, also from very bad and foul water, so that many die miserably."

The next paragraph recites yet another litany of woes before describing what sailing in a storm is like.

"When ... the sea rages and surges, so that the waves rise often like high mountains one above the other, and often tumble over the ship, so that one fears to go down with the ship; when the ship is constantly tossed from side to side by the storm and waves, so that no one can either walk, or sit, or lie, and the closely packed people in the berths are thereby tumbled over each other, both the sick and the well—it will be readily understood that many of these people, none of whom had been prepared for hardships, suffer so terribly from them that they do not survive it."

He writes that he was sick for a time, so he understood the suffering, and whenever he could he would hold daily prayer services. He baptized some children, held Sunday services, and officiated the burials at sea. Conditions were such that passengers became surly, stealing from each other and blaming those who had persuaded them to make the journey. Families would quarrel, and homesickness was as rampant as physical woes.

Children under the age of 7 suffered as much as any of them and most died. Pregnant women who died after giving birth would be thrown overboard along with the child. And he writes that one woman became trapped in the aft part of the ship and went into labor. A storm was raging at the time, and because of her position in the ship, no one could help her. She was disposed of by pushing her through a porthole.

To add insult to injury, if a passenger died after the midpoint of the journey, his or her family was still liable for transportation costs if they had not paid up front. Children whose parents died became responsible for the entire family's cost. The cost of the voyage ran to £10 for each adult and £5 for each child 5 years and older.

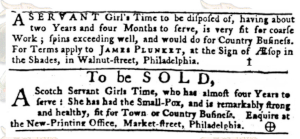

Many people seeking to immigrate could not afford the cost. Often these people would enter into an indentured servanthood agreement with a paying passenger, but the "man-dealers" mentioned above, whom he also called "traffickers" would make a deal with potential passengers that allowed them to make the crossing and be sold into indenture on arrival to pay for their passage.

Once the ship arrived in Philadelphia, these passengers were required to remain on board until they were sold in daily auctions. Adults agreed to a term from between 3 to 6 years, while children were required to remain indentured until their 21st birthday. Families were often separated in these sales, and some parents sold their children to cover their entire debt.

Mittleberger's book is available online, with excerpts detailing just the journey available in PDF for download.

Image: Ads for the sale of indentured servants. From latinamericanstudies.org.

Comments

Post a Comment